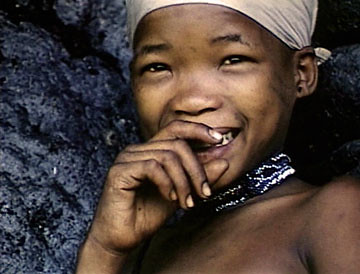

(A young John Marshall changing a film reel. I always thought he was cute.)

The theme for class this week was observational cinema. As sat and experienced my professors selections from anthropology heavyweights like David MacDougall, John Marshall and Jean Rouche, I found myself not only grateful that these men greatly understood the concept of a short film, but also thinking of how thankful I was for their contributions to the early years of the ethnographic documentary genre. These men proved that images on the screen could be as strong, if not stronger, than words in a book.

For over a century, anthropologists and social scientists have argued over which medium best represents an ethnographer's collected work: a book/written publication or a series of images. Now when I say I “experienced” their films, I'm referring to the fact that anthropological films cannot be, and were not meant to be, “watched.” Instead, they were created to provoke inquiry and inspire thought.

Marshall's “A Joking Relationship” is the perfect example of the ethnographic filmmakers equal, if not greater, obligation to maintain intellectual integrity than a normal ethnographer. The film visualized the kinship term for a relationship between two people, often of the opposite sex, who have a strong relationship rooted in playful mockery and sexual innuendo. For the Ju/'hoan bushmen of South Africa, this bond provides an emotional release that is stronger than most other familial relationships. Here we see N!ai and her great uncle-in-law engaging in a harmless flirtation as she jumps on his back while he threatens to cut off and eat her nipples.

At the end of the film, I noticed that it ends with a title card that reads “Directed by J. Marshall” (actually, as far as I can remember, this is on all his films on the Bushmen?). According to the Cambridge dictionary, a film director is “a person who is in charge of a film and tells the actors how to play their parts.” At what point does an ethnographer step away from being a data collector to being a data producer?

Marshall's editing and shooting techniques on "A Joking Relationship" redefine the role the ethnographer plays in creating a visual thesis. If there was a film dictionary of ethnographic terms, I feel like this clip would fit perfectly under its title term. He avoids the "fly-on-the-wall" feel by framing his subjects in extreme closeups, vignetting his observations by limiting what the viewer is privy too. At first, this method felt obtrusive and almost awkward as the camera panned across N!ai's exposed, undeveloped breasts and her great uncle's nether regions. Yet as the short carries on, I feel as though I'm reading a passage in a book. Marshall keeps a clear idea in his mind while he shoots with what he wants the viewer to see. He wants us to forget that we're about a hundred feet from the subjects, perched under a large shady tree in the Kahalari and keep us focused on nothing more than the intimacy, flirtation and casual sexual desire that carries on between the subjects. Marshall proves that a visual ethnographer and writer are one and the same. His pen is the camera lens: recording/writing a perfectly crafted anecdote on each frame/page, and then carefully compiling and editing it all together into a film/book.

If anything, I think the visualness of film brings to life something a great writer can never achieve. Descriptions become tangible as dances, rituals and forms of dress are exposed in their raw form. The fieldsite no longer remains an enigma; instead, the viewer can watch a film and be transported into subsaharan Africa and play the role of traveling ethnographer. Of course this isn't saying that all visual ethnographers are created equal not that every film is well constructed.

No comments:

Post a Comment